I Used To Be The Main Character. Then I Had Kids.

How fatherhood rewired my ego, my writing, and my sense of fulfillment.

We were trying to start the bedtime routine recently—bath, pajamas, teeth, books, etc. But it was late in the evening, my kids were tired, and they weren’t having it—especially my four year-old son. There were tears, lots of groans, and flailing limbs at the dining table. We proposed what we thought was a brilliant, if not psychologically exploitative idea: “Let’s race to the bathroom.”

Like a lightbulb had gone off between his eyes, my son shot up and sped off laughing. As he looked back to gloat at his lead, he slammed face-first into the corner of a wall. There was blood, a hell of a lot more tears, a late-night trip to the ER, stitches on his eyelid, and a doctor’s order to keep him out of school for three days.

The west coast work trip I had planned for the next morning (a trip where I was looking forward to some non-kid downtime to get writing and reading done) was canceled. The following 72 hours were reshuffled entirely: My wife and I quickly game planned to ensure one of us was home and available to keep an eye on my son, while also figuring out how to get our daughter to school on time, make meals, wash and fold the clothes, finish our work responsibilities, and generally keep the house running.

I wish I could say this was a unique experience. But the truth is, this sort of thing happens all the time now. Ever since I became a father, my days have been full of unexpected twists and turns.

For example, whether my kids will wake up in the morning wanting hugs and cuddles, or whether they will wake up swinging, yelling, and choosing violence is anyone’s guess. The odds of them so much as sniffing the strawberries I intricately slice for them at 7 a.m. is well under 50 percent. Getting dressed for school could either be swift and easy, or a prolonged hostage negotiation. Once they’re off to school, my day could proceed as planned, or I could get a phone call at 11 a.m. informing me my daughter has pooped twice in one hour and therefore (according to a team of non-doctors at her school) must be sick and needs to be picked up and kept out of school for the next two days (true story).

At any moment, things can change, and I’ve learned that a big part of being a parent revolves around learning how to deal with the curve balls.

This wasn’t always easy for me. Before I had kids, I was the guy with the to-do list longer than a CVS receipt. I was also the guy who could get thrown into a tailspin if there was so much as one disruption in my day that made me shuffle around that to-do list, or, worse, truncate it and feel like a failure.

But my kids have taught me how to become comfortable with disruption. Largely because ever since they arrived, my time is no longer mine. My precious goals and self-imposed deadlines are no longer set in stone and unmovable. My days have been reshaped by the needs of small, beautiful, and EXTREMELY irrational humans that I am charged with keeping alive.

I know that for many people the idea of losing this control and making your own needs secondary feels overwhelming. Even more so in our modern culture that prizes autonomy, optimization, and being the main character.

I get it. But from where I sit now, five years into this daddy game, I’m so grateful that my wife and I made this choice. I’m grateful that when I was 29 I didn’t let my fears about losing my autonomy or about not being a good dad because I had a shitty one hold me back. Not because parenting is some ultimate path to fulfillment for everyone—but because it’s the path that has just so happened to reshape me for the better.

Now, I won’t front. There are very hard days and there are downsides given that I’m a writer. For example, I probably write slower now than if I didn’t have kids (you might get dispatches from me weekly, for instance). I say no to cool opportunities all the time (if you want me to show up anywhere outside of Miami you need to pay me). I need a day job (those book advances don’t pay for daycare and health insurance, let me tell you).

But honestly, I wouldn’t change any of it. Because funny enough, becoming a parent—and all the responsibilities and limitations that comes with the job— hasn't stifled my ambition. It has only clarified it.

Perhaps the biggest gift fatherhood has given me—and my writing—is that it has helped me let go of my ego.

If you want to be a decent dad, or parent in general, you really can’t be the main character anymore. The experience fundamentally forces you to move aside, get out of your own head, and see the world through someone else’s lens—a lens, by the way, that is profoundly unique, naive, and often entirely unreasonable. This turns out to be great training for fiction, and for finding the humanity in your characters—especially the characters who aren’t your protagonist.

Another big gift fatherhood has given me is making me less tethered to outcomes and far less obsessed about the things that I cannot control. The uncertainty of my hours and days, the constant reshuffling that happens seemingly minute to minute, makes it quite easy for me to move on when things don’t break my way. I care way less about awards, about prestige, about being part of the “conversation,” and I believe my writing is all the better for it.

In fact, because I only have so much time in the day for myself, I’m far more focused on using the couple of hours I do have to chase what matters to me, which is creating work I’m proud of.

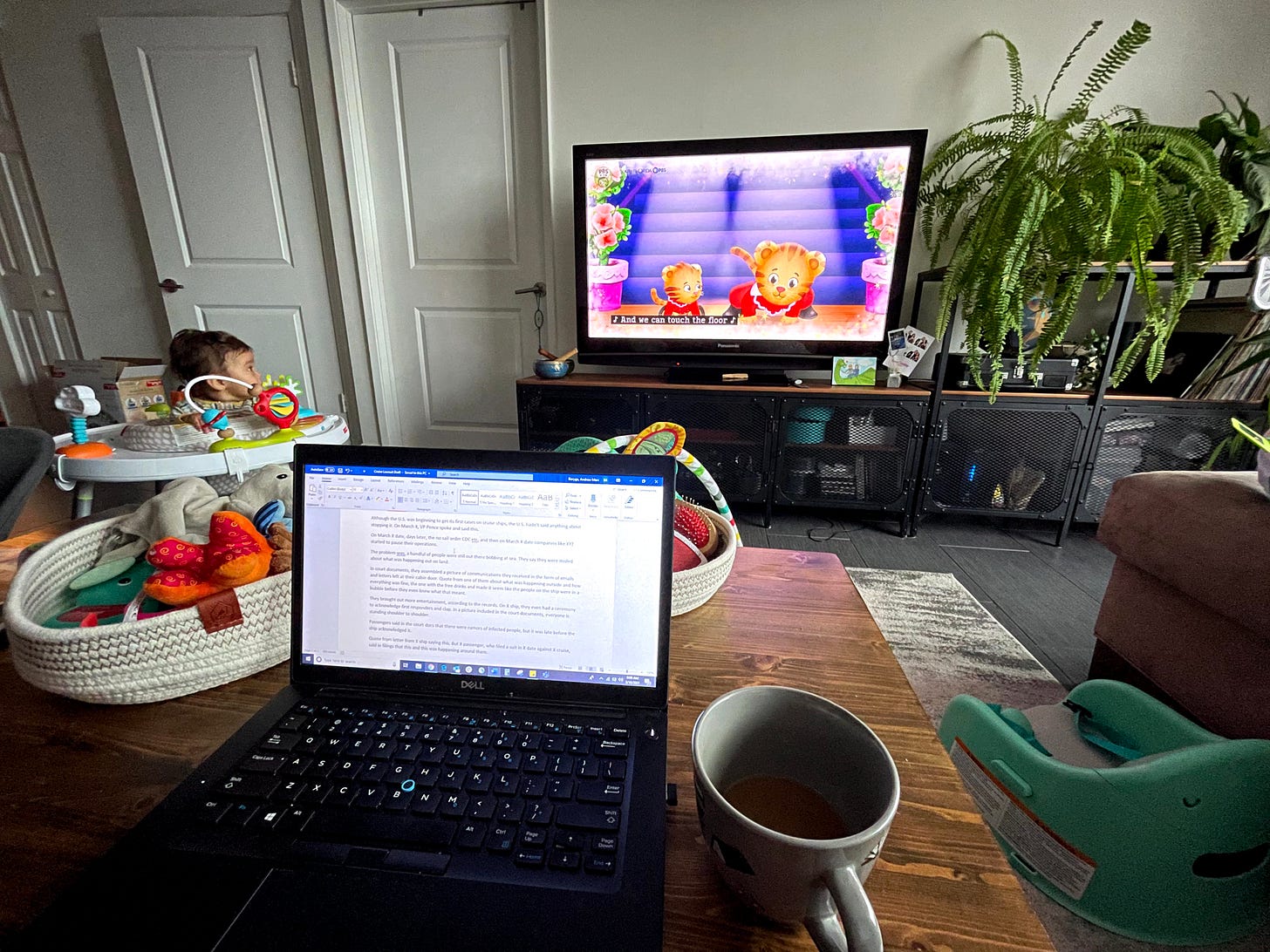

Even now, I’m typing this part of this essay at 6:45 a.m., racing the clock before my kids need to get up and the routine has to get going. The deadline and the scarcity of time, makes the experience so much sweeter.

I feel like a thief stealing this time for myself by getting up early each day. And as a result, I’m ruthless about how I spend it. I try to make sure (though I often fail, of course) that I spend it doing something that feels fulfilling and meaningful. So yes, I say no to a lot of things, but I also only say yes to the things that are the most gratifying.

On that topic, another gift this experience has provided me is profound fulfillment unlike anything I’ve ever known. This fulfillment doesn’t come from public recognition, or acclaim, or external milestones. It comes from the joy of seeing my son start to learn to read, or hearing my daughter sing to herself and knowing she feels confident and safe doing so.

It comes from saving up money to buy my kids the little backyard park I wished I had growing up in the Bronx where the manhole cover and the last rung of the fire escape served as my playground. It comes from taking them on new experiences and watching their faces light up. From getting long hugs. From feeling like a superhero when I change the batteries on their toys or staying up late building something for them and watching them go nuts when they see it in the morning.

These pure moments make everything else that comes from the literary world—awards, acclaim, outcomes—feel more like icing than sustenance. Which, given the fact that all those things are so damn arbitrary and up to the whims of others and big corporations, feels far more healthier.

I know what some of you are thinking by now: Are you telling me to have a child to fix all of my problems? No.

I’m not trying to make an overt pitch for parenting, although I can’t lie: I do wish more people my age had the chance to experience the deepening of humanity that comes from parenting, and I suspect it would make a lot of us more grounded, humble, and willing and able to embrace uncertainty. But I’m not naive or some raging pro-natalist. I know there are very real barriers and very valid reasons people choose not to have children.

On this Father’s Day, I just felt it appropriate to reflect a bit on what this path has done for me, personally. I’m also thinking a lot about this because I’m writing about it, too. My next novel explores themes and questions around fatherhood, masculinity, modern domestic life, and what happens when the tools we use to make parenting easier start to shape us in unexpected ways. There will be more on that soon, or relatively soon, who knows.

But in the meantime, I also want to use this piece to take a moment to shout out the dope dudes out there that I see doing this same writer-dad dance I’m doing. People I’ve come to know online like

, , , , Frank Santo, Andrew Lipstein, D. Watkins and others I’ve got to know IRL like , , Juan Vidal, , Joseph Earl Thomas, and Dwyer Murphy. Dudes who are just as involved and in it with their kids as they are with their words on the page.Growing up, I can’t say that many of my literary heroes were known to be good dads, or, at the very least, trying to be good dads. In fact, it sometimes felt like being absent from your family, eschewing the idea of having a family, and being completely selfish with your time and whims, was part of the male genius myth.

But I fucking love that there’s a new image forming now: Dads who show up on the page and who show up at daycare drop-off, at the doctor’s office, in the laundry pile, in the middle of the meltdown.

This balancing act is tough for all parents—and it should go without saying that it’s almost always way, way tougher for moms, who, no matter how much more involved men are these days, still tend to end up carrying more of the load, mental or otherwise.

But I’m just happy to see a lot of writer-dads out here trying hard to carry more, to do more, and to rewrite the role in real time. I really think that is beautiful.

So, with all that being said, Happy Father’s Day to the writer-dads out there doing their thing. Happy Father’s Day, as always, to the single moms out there doing double duty (Father’s Day is for you, too). And a special Happy Father’s Day to those dads figuring this all out in spite of the shitty or non-existent models we had ahead of us.

As Kendrick says: “I salute you, may your blessings be neutral to your toddlers.”

Peace,

Andrew

Before having kids of my own, I felt sorry for writers with kids. They had so much less time, and a different set of priorities. I assumed this made them inferior writers. Then I became a parent, and I realized--it's ok to care about other things. To put family above myself, and my books. I'm sure I could've written a few more books if I didn't have children pulling my attention in a million different directions. But I'm not actually sure they'd be better books. Children open your eyes to a wealth of new experiences and emotions. This has the potential to make you a better writer with a deeper well to draw from.

Great post!

"This turns out to be great training for fiction, and for finding the humanity in your characters—especially the characters who aren’t your protagonist." Hell yeah! (Also love that this arrived in my inbox exactly as I'm working on an essay about protagonist syndrome and life not imitating art.)