A Conversation with Novelist Andrew Lipstein

Chopped it up with the author of the recently released Something Rotten.

Something I’m looking forward to doing more of in 2025 is showing love to books and authors making their way out into the world this year. One way I plan on doing that is to run some Q&A’s with authors whose work I appreciate.

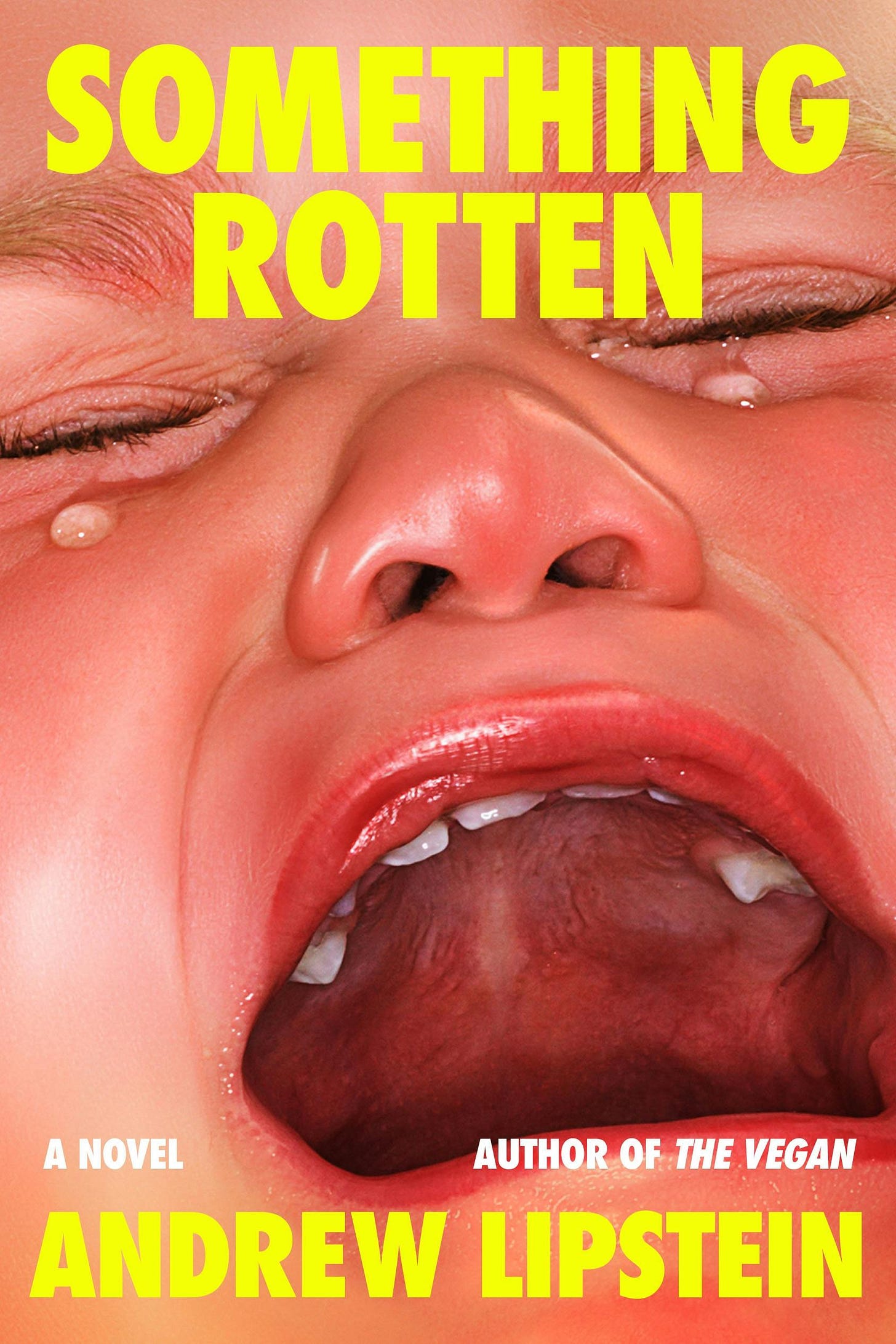

Andrew Lipstein is one of the first writers I thought of reaching out to for this new endeavor. Not just because he has a new novel out this year, Something Rotten, published last month by Farrar, Straus & Giroux, but because I’ve long been a fan of Andrew’s work—and his work ethic.

In addition to his latest novel, he’s also the author of two other well-received novels Last Resort (2022) and The Vegan (2023)—an output by a young writer that is impressive on its own, but even more so when you take into account that Andrew has three kids and a day job (really, what is your excuse, dear reader?)

Prodigiousness aside, I appreciate the way Andrew uses his fiction to not only create compelling stories, but wade into big, thorny questions and themes. He also has a knack for crafting complicated, morally ambiguous narrators, and seems less interested in you walking away liking these characters than he does in interrogating their gray areas on the page.

Something Rotten follows two relatively new parents, Reuben and Cecille, during an extended vacation to Copenhagen. The trip comes on the heels of Reuben’s cancellation from NPR, and a leave taken by Cecille, a reporter at the New York Times. Back in Cecille’s home country, the pair fall in with her old friends and discover that her ex-lover has been diagnosed with a fatal illness. While Cecille is busy tending to her old flame, Reuben finds himself rapt by the influence and masculine posturing of Mikkel, another one of Cecille’s friends, who causes him to dwell on the differences between being a man in America vs. being one in Denmark.

The novel takes on themes such as masculinity, parenthood, infidelity, and the ways in which a change in scenery can fundamentally reorient the way you think. Andrew and I chatted over email about his new book, his work ethic, process, and more.

What was the inspiration for Something Rotten? Do you remember when the germ of the novel first struck you?

This was by far my most plotted out novel, and it really came together from three almost entirely distinct ideas. The first and biggest was something very crazy that I realized would be hard to justify, and that justification became the bulk of the novel. I know I’m speaking elliptically here but that’s because the germ of the book was the twist itself. I will say there were certain ideas—about mortality, authenticity, truth, masculinity—that have been on my mind for a while and informed those major plot points.

Inspiration-wise, it really came from my time in Denmark and the people I know and met there. In fact, I outlined the book while living in the country, in the winter of 2022.

Was there anything interesting that came up in the drafting process that forced you to detour from initial plans you may have had?

I don’t like restructuring books. In fact the very idea that I will have to do a complete rewrite of a book makes me feel like a child who just got in major trouble. My heart stops. I am very intentional in the sequence of chapters while I’m writing, and I always write linearly.

Whenever I hear someone talk about writing an exploratory draft or trimming down a long novel into a short one, it’s like they’re speaking martian. I want to be inside their mind to understand what would bring someone to do such a thing, but at the same time, I definitely don’t want to be in their mind.

A big thrust of the novel are the differences between American masculinity and Danish masculinity that Reuben notices. What are some big differences you noticed between both “performances” of masculinity in each country that you wanted to explore?

Someone recently described it as thus: in America, masculinity is far too over examined and overanalyzed, and in Denmark the concept suffers from the opposite problem. I don’t think this is far off. It at least captures the fact that neither place gets it right, and often the most sane way of viewing anything is with shades and balance.

In America, I think a lot of men feel they have to apologize just for being men. In Denmark, perhaps, there is less thought that goes into the inherent privilege of being a man. These are (over)generalizations; that must be said.

I’m already lawyered up, for those interested.

Speaking of masculinity—and performances of it—I’m curious what interests you most about modern manhood in the U.S. What questions were you circling around?

What’s most interesting to me about masculinity today is that the very earnest, toxic, unironic version of it has won the day, at least as of late. Most devastating to me is that this version of masculinity is fear-based.

What people on the right believe is that to be a man you have to be like this or that. Where a more liberal concept of masculinity can succeed is being more imaginative, open-ended, and freeing. Any concept that defines how people are is best when it eliminates constraints, not builds more of them.

There are a lot of journalists in Something Rotten, some of whom resort to unsavory practices for what they believe are righteous ends. What role did you want the media to play in the novel?

The idea of journalism is important to the book because it has two seemingly mutually exclusive and yet completely intertwined aspects to it: values and practical action. I don’t know of any other profession (law, maybe?) in which the abstract and concrete mix so thoroughly on a day-to-day basis.

If you’re reading this and you want to know why this is important to the book, well, just buy a copy. Two if you must.

Taking into account your previous work, it’s clear you’re drawn to narrators who are morally ambiguous. Why is that?

Is there such a thing as a morally unambiguous character? Seriously. Is there such a thing as a morally unambiguous person? Certainly not.

So why would I want to read about one!?

A while back I discovered your interview ingenious series, “Thick Skin,” which gives authors the chance to respond to bad reviews of their work (here is the first installment featuring Sheila Heti). You’ve received some uneven reviews for Something Rotten. What are your critics missing?

If I get a negative review it’s usually because the reviewer is a dolt who probably lives a sour life and doesn’t enjoy good writing or thought-provoking storytelling.

I wish them well.

Something Rotten is your third book in four years–which is an impressive output for any author, let alone an author with kids and a job. How have you been able to work at such an incredibly fast clip?

Actually, it’s my third book in three years.

Like Michael Crichton or John Grisham I have a sort of factory system, but instead of people I pay to do the work it’s just myself I control and order around.

Think about it.

Most of my readers are emerging or early-career writers. Now that you are three well-received books into the game, what advice do you have for others trying to find their own way?

Kill your ego. Write only what you want to. Be prudent. Cast a wide net. Treat your writing career like a career.

Also, as you gain advocates et cetera, remember that you’ll only ever have one true advocate, and that’s yourself.

There you have it folks. Many thanks to Andrew for chatting with me! Now please, go buy his book.

Peace,

Andrew

Based on his answers, I suspect Andrew and I would get along.

Great interview -- adding the novels to my queue.

Ahhh! One, I love that you’re doing interviews especially since our taste overlaps so this will be extra exciting for me 🤭 Two, loved this conversation. His thoughts around masculinity and criticism are spot on 🎯 hahaha