Live from Sing Sing: A Q&A with John J. Lennon

An incarcerated journalist dials into a Miami bookstore.

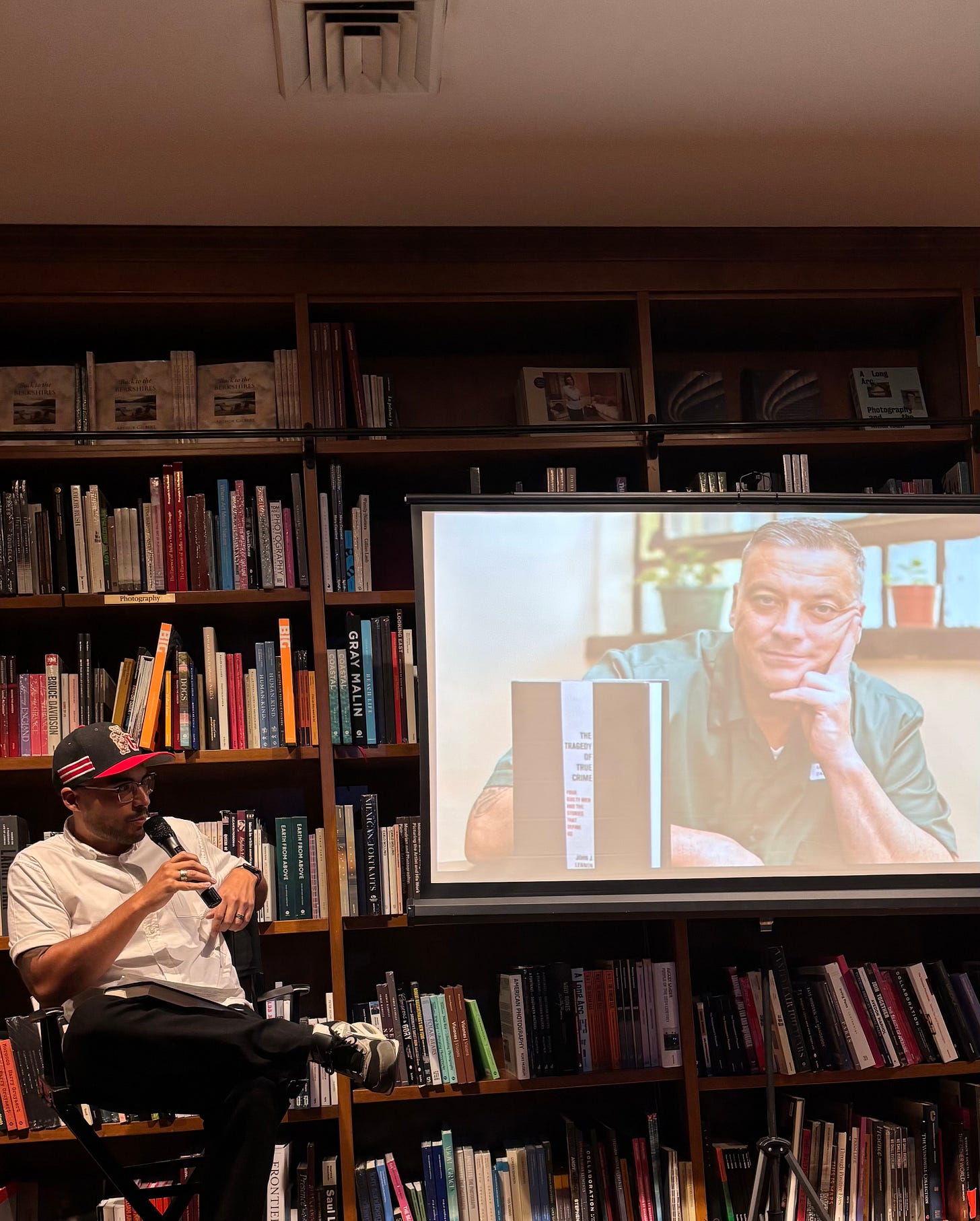

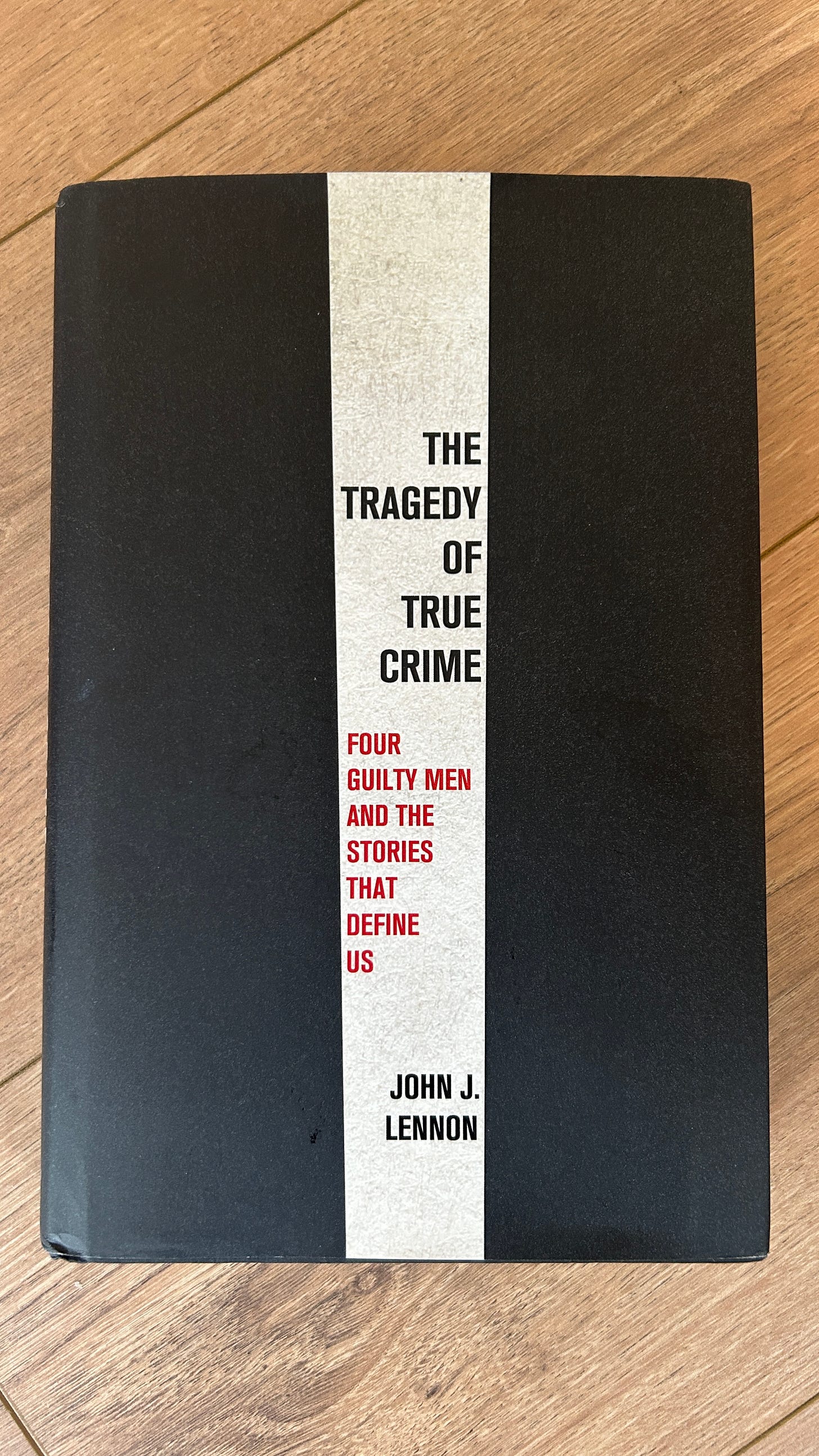

On October 2, I had the privilege of taking part in one of the coolest literary events of my life. At Books & Books–the Miami literary institution and independent bookstore–I interviewed John J. Lennon about his debut, The Tragedy of True Crime: Four Guilty Men and the Stories That Define Us.

I’ve moderated plenty of events at Books & Books, but never one like this. I was on stage by myself, save for a screen broadcasting an image of John’s author photo. That is because John is currently incarcerated at Sing Sing, where he’s served 24 years of a 28-to-life sentence for killing a man in 2001.

With help from his devoted publicist Megan Posco and the Books & Books staff, we routed a call from his cell block through the store’s speakers. Technical hiccups early on in the event made me to stand and lean toward a laptop as I posed questions to a glowing screen and a voice I couldn’t see. But the strangeness only made the event more powerful. Around 35 people showed up and we all sat in a kind of collective stillness, listening intently to John’s voice. It was a communal, reverent experience that I’ve never before had in a bookstore.

Speaking of firsts, I don’t know of another incarcerated writer ever doing a book tour like this either. And the fact that people came out to hear John talk about his life and his work—which has been published everywhere from The New York Times and Esquire to The Washington Post and The Atlantic—felt like being part of a small piece of literary history.

The night was made even more special by an introduction to the event made by Kathie Klerrich, executive director of Exchange for Change. The writing courses Exchange for Change offers incarcerated people—which are similar to the class John took in Attica in 2010 that launched his career—are life-changing. Teaching for Exchange for Change was a highlight of my own life, and seeing John’s success, along with that of my former students, is a testament to what these programs make possible.

As you read this, Miami is celebrating Give Miami Day, which is a push to raise funds for excellent nonprofits in the city. If this Q&A moves you, and if John’s story speaks to you, I hope you’ll not only buy his excellent book, but consider donating to Exchange for Change. Last year alone, they helped more than 600 incarcerated men and women discover the power of writing in South Florida.

Aight. Off my soap box now to present the Q&A between myself and John on October 2, which John graciously agreed to me recording and sharing. And damn am I happy I did that.

Since we can’t see you right now, I was hoping you could tell us about what’s around you. Where exactly are you calling us from in Sing Sing?

I’m in a booth because the landline is clearer here. The other half of this tier I’m in are guys who suffer from mental illness. They put the guys that kind of have their acts together in prison with the guys that are suffering a little. The idea is that we can sort of understand what they’re going through and give them some grace. This is actually the tier in 2017 in which I interviewed Michael Shane Hale, who is featured in my book.

How does it feel to be on a virtual book tour in prison? I’m not sure this has ever been done before. Who came up with this?

I don’t know. This whole career is crazy, man. As a prison journalist you kind of have to develop relationships on the outside to make things happen. Megan Posco, my book publicist, had reached out to me years ago when she was publicizing my mentor Bill Keller’s book, and she started helping me with some of the freelance stuff I was doing. Then the book was coming out, and I knew that she knew the ropes so she figured that we could actually do this. She kind of created the tour and arranged all of this.

So, yeah, I don’t know that this has ever been done before, but it’s a trip. I’m grateful.

It’s pretty special. So, let’s get into the book, starting with the germ of it. You write in the book about this episode of Inside Evil, a television show you were featured on, where you were interviewed by Chris Cuomo about your crime. Can you tell us more about that experience and how it led you to come up with the idea of writing this book?

I’m a personal journalist, so I write about things that I experience first hand. Prison obviously being one of those things. I came to prison in 2001 when I was 24-years-old. I was a dopey kid, and I had just killed a man, and I had been involved in this drug-dealing lifestyle.

Eventually, along the way, I learned how to write at a workshop in Attica. I took to journalism, and I started writing a lot. Fast forward several years. By the time I was transferred out of Attica and had come to Sing Sing, I had been landing features in magazines. I was just writing about what I like to think were important issues. Things like mental illness in prisons, people trying to get an education in prison, sports betting in prison, fashion in prison. I mean, just whatever. I was trying to bring people into this world and I had kind of found my niche.

And then this show came around, seeking me out. And even in the book I say that I didn’t go looking to be a critic of true crime, true crime came looking for me. These producers came to me and floated this idea for a show, but they were being vague. And then when they came to visit me I confronted them about it, because I found out the show was called Inside Evil, and they said no, it’s going to be about redemption and so forth. It was a total schmooze game. They clearly saw me as a murderer and not as a journalist, and that came through in the final episode.

I used my experience of being on the show and dealing with these people as an entry point to this whole genre. I started writing criticism of true crime, but then I proposed this book thinking that maybe I can do this better than them. Maybe I could tell these stories with a little more heart. You know, what happens after the gavel drops? What happens day to day here? That’s what I tried to do in The Tragedy of True Crime.

The book concerns the lives of four men, including yourself, and details who they were before their crimes, and who they’ve become since. You say you set out to record the “felt lives” of these men. What does “felt lives” mean to you, and why do you believe it’s important to include them in these stories?

Well I had that sort of access to show the felt lives of these men. And what I mean by felt lives is this style of journalism that I started writing for Esquire. I started working with these editors that had really been steeped in Esquire’s history of new journalism and that helped me achieve these really character driven narratives. It’s the style of journalism I took to. I guess it’s also called immersive journalism.

After I started writing, I figured out that because of where I was I actually had access that no other journalist really had. And so I decided to try and merge that access with this narrative style of writing I was learning while working with these great editors.

So when I say felt lives, I really mean intense observation. I live with these men, I see them, I see their daily routine. And I thought that was really important to capture. And in fact, that’s how I introduce the reader to these guys, as opposed to the traditional structure of true crime.

I mean, we all watch it right? We know how it’s structured. It’s the 911 calls, the crime scene photos. The world delivers the facts. And as narrative storytellers, how we choose to arrange those facts is very, very important. So, I didn’t want to introduce you to these guys as they are traditionally introduced in true crime. I focused on the style I had been developing, which is quite different from the newspaper style. It’s very first person. I had to kind of bring you to the scene and inside the walls. And I thought people would want to see that, and want to know these things. It’s a slow grind until we get to where each of these men are, what they do every day, and then we drop back a bit and get to see how each of them grew up and so forth. And then we get to the crime. And even though I’m taking my time, I don’t hold back. I tell you what we all did.

The book is narrative heavy, but it is also deeply, deeply reported. You spent many, many hours with each of these men, tracked them down when they were transferred to other prisons, interviewed family, victims, etc. Can you talk about that reporting process? How the hell did you pull all of that off?

Well, for one, there are no recording devices allowed in prison, so it’s usually just a pen and pad. It’s old school. When it comes to the reporting itself, I mean, sometimes you’re meeting people in the yard, you’re meeting them in the basement of the cell block, you’re meeting them wherever you can meet them. You’re often on display to the rest of the population, too. So it is a bit of a high stakes environment.

Then there is the outside reporting. I made a point to reach out to experts, to the family members of my subjects, and even some of the family members of their victims. I do it all like I’m doing it right now, talking to you guys. When you’re writing from where I’m writing, you gotta be creative in the work, but also in the craft of reporting.

Once I got my book deal, I hired a research assistant and another assistant, and they helped track down people for me on the outside. Then during my interviews here, I would take hand-written notes and then use a typewriter to transcribe them and stuff them all in these folders I took with me from cell to cell. Eventually we started to get these tablets in prison, which has made the process a bit easier.

Still, I had to be creative. When I needed to speak to someone in another prison, I would do these things we call “Boomerang Calls” where you call somebody, and the person in the other prison calls that person at the same time and the middle man merges the calls and we can speak to each other.

So yeah, you gotta get creative to do what I do.

At the very least, everyone in this room tonight will leave with a newfound understanding of what a boomerang call is. Now, how did you settle on these three men to profile? What made you want to focus on these three lives in particular and paint them with the nuance that you did?

Well, for one thing, the crimes were all different, which I liked. But it was also about the connection that I had with these guys, as well as what each of us represented. I looked for conflict. Conflict is the most important element of story, right?

So, for example, I look at Michael Shane Hale. He’s a gay man in prison, which, for those that don’t know, the most marginalized people in prison are gay people. It was high stakes for me to even talk to him and hang with him and immerse myself in his story. Despite that, we became friends over the course of my reporting, and that’s something I disclose in the book I evolved and I tried to capture that because I was a character, too. As I got to know him, I realized I wanted to tell his story. I felt like I was the best person to do it because people don’t really know what it’s like for a man like him to do time. At least in New York prisons. Gay men who are out like him are very ostracized.

Then there was Milton E. Jones. He was a young man when he came to prison. Only 17. He killed two priests in 1987, and by the time I started speaking with him in 2015 he was pushing 50. He had been in prison for nearly 30 years. He was living with severe mental illnesses–psychosis, schizophrenia. And despite this, he took his medication and he pursued his education: a master’s degree in theology. I thought everything about him was so complicated and admirable, and I wanted to know more about his story.

Then when I transferred out of Attica and met Robert Chambers in 2020, he seemed like a clear choice to me because he was a true crime celebrity, and not of his own desire. In 1986, he killed Jennifer Levin in Central Park and got dubbed the “Preppy Killer” and was written about all over the place and had multiple documentaries made about him. I wanted to show who this villain was that everyone loved to hate (and by the way, he hated himself, too). I wanted to write about him and show a bit about what it feels like when the press tells you who you are.

You know, I had this one show made about me, and it bothered me so much that I went and wrote this whole book. I have a voice, and I have had the ability to put my experience with this show in a lot of legacy magazines. Those producers probably regret coming to do a show about me at this point. But my point is that most people never ever get to see the other side of this. What’s it feel like to have a true crime show about you? What does it feel like to see one version of your story on the television screen, and to know that everyone else in your cellblock, as well as millions of people at home are watching it?

So, these are all different stories and they all have different themes. And then there is my story. My story is that of street crime; a street life story. I was a punk. I was a wannabe gangster and drug dealer. I thought that each of these men, as well as myself, represented a nice mix of identities and backstories and themes: Sexuality, mental illness, loss of innocence, true crime celebrity, street life. Between all of us, I figured we could capture a pretty wide swath of the type of people you might find in a prison.

You note that true crime has never been more popular, even though murder rates are the lowest they’ve been in decades—and you’ve even been in prisons that have closed due to low populations. Still, people are binging these stories and going to bed with them. How do you make sense of that disconnect?

The FBI came out with the stats recently. It’s just a fact: If you’re 50 or younger–despite what you hear on cable news or read about online–you are in the safest time period in this country in generations.

But despite crime rates being so low, more than half of Americans believe the opposite to be true. Why is that? In my opinion, it’s all narrative. Around 57 percent of Americans say they consume true crime content, which means a lot of people are watching stuff or listening to stuff about murder before they go to sleep. Well, I have a hunch that many of these people who go to sleep watching shows about murders probably wake up very grateful for prisons, right?

So it’s really about narrative. I don’t trust those true crime stories to frame that narrative for me. And I’m here to say that you probably shouldn’t either. Now, you may say, well, why would I trust you? Well, my answer is that I give you no reason not to. I’m relentlessly honest. I leave it all on the page.

You write in an essay for the New York Review of Books that part of being a reliable narrator is “offering ourselves up for judgment. That means being honest and vulnerable, which is tough, because to survive prison you have to be guarded.” Can you say more about that tension and how it played into the writing and reporting of this book?

I mean, I’m being vulnerable on the page when I’m in my safe place, which for me is in my cell, writing. For me, writing was where I was able to get real with myself. And thank God I found writing, because there isn’t really much help for you in prison. In the 24 years that I’ve been locked up, no one has ever tried to help me work through the fact that I’ve killed a man. None of that stuff is going on with your tax dollars. Just FYI.

There’s the yard, and then 23 hours a day in your cell. That’s what happens in maximum security prison. Particularly now because it’s not really a desired job and there are a lot of staffing issues.

Writing has been my refuge. Because I’m a personal journalist, I knew that if I’m going to write stories about life here, I first had to come clean. And a lot of times, I came across as too cavalier about my crimes. I look back at my early writing and now, you know, 15 years later I’m just like eh.

You evolve as a writer, thankfully. So I have written deeper essays since, about the what of it all. And I have to say, to your question, what brings me pride–which is writing, and this career I’ve built, which perhaps culminates in this moment, who knows–also happens to cause the family of the man I murdered more pain. It causes me shame at the same time.

So I’m in this moment where I’m writing a really controversial book, taking on an industry, and doing a pretty bold thing. But to be honest, it doesn’t feel like all pride from where I’m sitting. There’s shame, too. And that’s because of the conflict of it all. Because of the remorse.

You mentioned writing being your refuge, and I was hoping you could speak about the earlier experiences you had with writing in prison. You mentioned a workshop you attended in 2010. Can you tell us what happened for you there that changed things?

So, I had just gotten stabbed in 2008 pretty bad. I ran into a friend of the man I killed and he hit me up pretty good. I was in a different prison, closer to New York City. He got away with it because I didn’t tell them who did it, so they transferred me to Attica.

I had briefly been an addict there. Attica is a tough joint. But there was this silver lining. They had a good AA program there, and I went to the meetings and I kept hearing about this writing workshop. I loved stories. I was always the guy watching the movie who knew what was going to happen.

The issue was that in prison, where there aren’t a lot of good things going on, when there is a good thing going on prisoners kind of become gatekeepers. So it was hard to get into the workshop at first. People are sizing you up. Eventually, I did get in. There was this professor who came in to teach us and he was pretty non-fiction based.

AN AUTOMATED PRISON VOICE TELL US: “YOU HAVE ONE MINUTE LEFT.” THERE ARE AUDIBLE GROANS IN THE CROWD, UNTIL I LET THEM KNOW JOHN WILL CALL US BACK.

This guy exposed us to all this great non-fiction work, and where these essays were published originally–in places like The Atlantic, The New Yorker, Esquire, The New York Review of Books. So I was sort of like, okay, if that is where all the great writing is, then that is where I’ll go. So I started subscribing to these places from prison, and I became an autodidact, essentially. I just started taking writing very, very seriously. And I appreciate that workshop because it pointed me in the right direction. It exposed me to what good writing looked like.

CALL CUTS OUT. ABOUT TWO MINUTES LATER, JOHN IS BACK ON THE LINE.

For someone here tonight, or someone who discovers your book after its New York Times review, who might be skeptical and think, Why should I read a book by someone who committed a grave crime? How do you respond to that?

It’s a fair sort of skepticism. I get it. I would say for one, a lot of us, myself included, will be getting out of prison one day. And, in fact, if there was a different temperature in the air, or if I was in the feds, or locked up in a different state, I probably would have been out already. But the larger point is that 95 percent of people who go to prison get out of prison, and I would think that people would be interested in hearing from us. Especially from someone like myself who has gone through the sort of arc of change that I’ve gone through in my life.

I happened to find myself despite being in a pretty tough environment, and I just hope that resonates on the page. People are people. I understand that some of us may have had some pretty awful transgressions, but you know what, we may be living with you one day. We may find ourselves back out in the world, trying to make our way. So why not hear from us? Why not give us a chance? Why not?

BONUS: AUDIENCE QUESTIONS. EACH AUDIENCE MEMBER APPROACHES THE LAPTOP SCREEN WITH A MIC TO ASK THEIR QUESTION.

How have your fellow inmates reacted to you writing this book? Have they read it? What kind of feedback are you getting from them?

You know, I talk about being vulnerable and leaving it all on the page, right? But the reality is that when you’re a writer like me and the work is not yours to tinker with and it goes out there, you’re still living in a very high risk environment. You’re like, Oh man. Maybe I shouldn’t have wrote that. Or, I don’t know if I really expressed this like I meant to. There’s a lot of fear on my end in that equation. But believe it or not, there is a lot of grace on the end of the guys in here.

There are some friends of mine here that I gave the book to and that I was fearful of reading, but honestly I’ve been going through that experience for years. I think it’s kind of like how it is out there. You may have people that like your work, and you may have people that are skeptical or don’t like it. The irony of it all, is that some guys here may see me as somebody who is using others for their story, despite the fact that I’m calling out the true crime story genre. Sometimes I get a little flack, which is kind of hurtful. But then sometimes you end up inspiring people, too.

I hosted a workshop last year, with the help of my publicist. And seven of the nine men went on to get published. That’s a pretty big deal for guys in here that are wrapped in walls, you know? You feel irrelevant and suddenly you become relevant, even if for a brief period of time.

So, the response is a mixed bag sometimes.

Who are some of the writers that inspired you?

I mean with this book, I was really inspired by Emmanuel Le Carre. He wrote The Adversary. I love this guy’s style, and he was all about telling the truth on the page and writing about how he feels and occupying his position. It was a fascinating way in which he narrated that book and I highly recommend people check it out.

Then, of course, there are books like Norman Mailer’s The Executioner’s Song, Tom Wolfe’s The Right Stuff, Janet Malcom’s The Journalist and The Murderer.

So, yeah, there have definitely been some great books that have inspired me. But I also love the great new journalism, too. You know, Gay Talese, Joan Didion, a lot of those great magazine writers.

Do you see your incarceration as an opportunity to get where you are now as a writer? What do you think would have been doing now, had you not been incarcerated?

That’s a tough question, right? At the heart of it, it’s like: This guy clearly has some talent as a writer, but did he really have to kill a man and come to prison to find his way? And you know, I really don’t know. To be honest with you. I don’t know what I would be doing.

But look, what I can say is that I wouldn’t recommend this path to you. It’s not a path where I would say, hey, you know, there are actually some opportunities for you in prison. The truth is that I got lucky. I hit some green lights. I had some good timing. I received the grace of a lot of decent people.

I got into that workshop in Attica around the time that people were really disgusted with overstuffed prisons in America and I took a shot. I took a shot and it worked out. I’m the type of person that you let someone like me in the game, I’m going to go for it. And, it’s also important to mention that at the time, I was at ground zero. I had fantastically failed at life. I had ended up in Attica with more years to serve than I had lived on this earth. I mean, it can only go up from there, right?

Sometimes, you get a little lucky, even in an awful environment.

What are you hoping people take away from this book? From this event?

I just want folks to maybe think about the stories they consume and how it affects them. Think about who’s telling them and who gets to tell them, and how truthful they are. I think there are a lot of talented people out there telling these true crime stories. But I would hope that audiences would welcome a new voice into the fold. Because perhaps I could offer a different perspective and maybe folks can feel something from that.

I think the point of art isn’t to answer questions, but to ask them. So maybe on the way home this event sparks conversation. Maybe you say to yourself: What did you think of that? What do you make of that? That’s a good thing.

This article comes at the perfect time, offering a profound reflection on the evolving modalities of literary engagemnt and the inherent power of storytelling to transcend physical barriers. As someone who deeply values the comunal aspect of sharing narratives, akin to the shared focus in a Pilates class or a book club discussion, this account underscores how human connection can be forged even through the most unconventional interfaces.

Such a good interview! Looking forward to reading this book